That's what both unions reps and their contractor counterparts charged yesterday at a lengthy oversight hearing yesterday (link to video) on modular housing held by the City Council's Committee on Housing and Buildings. And some said it was done at Forest City's behest.

"So, the bottom line is we're compromising safety for the bottom line?" asked Council Member Letitia James at one point.

"When it comes to exempting modular housing from the requirements of the [Building] Code, I think the answer to that is yes," replied Stewart O'Brien, executive director of The Plumbing Foundation.

|

| Council Chairperson Dilan |

(DOB did not respond to my late-day query for comment. Forest City directed my query to DOB.)

Committee Chair Erik Martin Dilan, who took pains to say he favored affordable housing and couldn't speak to any alleged intervention by Forest City, stated, "But what I do see occur is clear non-compliance with the code. We will ask the Buildings Department and the Mayor's Office why they think this has occurred, because I think it should be corrected."

Dilan also observed that the hearing "is being done without fanfare, without press." Most attendees at the hearing, held at 250 Broadway near City Hall, were union members. Forest City's lobbyist was one of the few who stayed all 4.5 hours.

|

| Graphics from Forest City presentation |

The hearing exposed a lingering fissure in union ranks over the Atlantic Yards modular plan. When news of Forest City's plans emerged in March 2011, several unions expressed dismay and concern about compromised safety and lowered wages, especially since they'd vocally rallied for the project.

Since then, Forest City signed a deal with the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, whose president, Gary LaBarbera, said at the groundbreaking last month, "It will create union construction jobs with good wages and benefits that may have been at risk if not for the strong labor-management partnership that exists between Forest City Ratner and the Building and Construction Trades."

At the hearing, longtime supporters of Atlantic Yards affordable housing, including former ACORN head Bertha Lewis, forcefully urged faster adoption of such prefabricated techniques, seeing it as a solution to the housing deficit. (The Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding ACORN signed also obligated Lewis to support the project.)

As those testifying critically about the DOB were mostly beefy white guys of a certain age, Lewis, a middle-aged black woman, made scornful reference to the building trades' history of excluding people of color. (James, a critic of Atlantic Yards, skeptic of the DOB, and supporter of affordable housing, later uttered the obvious: "There's a subtext... the issue is obviously race and class.")

Also submitting testimony in favor of prefab construction was the powerful Real Estate Board of New York, which said Forest City's innovations--adapting modular for high-rises and working out an agreement with unions--could "be an important and effective way to address our city's chronic shortage of affordable housing." The Association for a Better New York, another business group, also supported modular.

Lower wages but other benefits

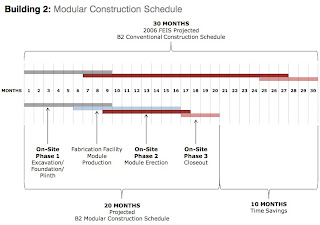

Forest City hopes to ultimately save 25% off conventional construction, thanks to lower wages in the factory (operated in partnership with Skanska at the Brooklyn Navy Yard), higher productivity in an indoor setting, and time savings--20 months vs. 30 months--by working simultaneously on-site and off-site. Some 60% of the tower will be constructed off-site.

"They get paid less," Forest City's Melissa Burch said of the 125 union factory workers, "but there are benefits to that. They have a steady, 40-hour-a-week job, and to the extent this is successful, they will be working in the factory 52 weeks a year."

They will be cross-trained, so carpenters, for example, will do tile work and put in electrical components. "We hope this is a long-term solution for Atlantic Yards," Burch said, and "a new business for New York City." The job would be safer, create less waste, and cause less community noise and disruption. The first building is aimed for LEED Silver.

Dilan asked about the wage difference.

|

| Forest City executives (l.-r.) Cotton, Burch, Sanna |

"I don't know that it's necessarily half," followed up Forest City Executive VP Bob Sanna. "We have negotiated an average wage in the factory that is approximately $36 an hour, with benefits." He said that's "completely in line" with other manufacturing of building components and that the rate "is probably 10 or 15% less than if the person were employed on site."

That later drew a heated response from John Murphy, Business Manager of Plumbers Local Number 1, who said that the wages were actually 70% less than those for plumbers, who must go through more than 1,000 hours of classroom training and 10,000 hours of on-the-job experience.a lengthy apprenticeship and training system.

Forest City's plan, he said, has "the potential to turn a very highly skilled trade that takes years of training, practice, and experience into unskilled assembly work," which could be shipped out of state. (Council Member Lew Fidler, a longtime Atlantic Yards supporter hand, suggested that the Council find ways to "incentivize" local fabrication.)

James asked at one point, "If this were built conventionally, how many union members would there be on site?"

"I don't have those numbers on me," replied Ashley Cotton, Forest City External Affairs VP.

The developer has long been fuzzy on an apples-to-apples comparison. At a public meeting last November, Burch stated that “Modular construction will require approximately the same number of man-hours as conventional construction."

However, Cotton could not answer how many construction workers were needed to build the building in terms of job-years, a common term used to evaluate jobs promised for the project. (Projections included 15,000 job-years and 17,000 job-years.)

Nor has there yet been a comparison between the promised construction workers benefits (compensation x job-years) and those currently contemplated.

Code change?

|

| O'Brien (l.) and Murphy |

"In April 2011, the DOB issued a Bulletin [bottom] which seemingly allowed employees of non-licensed firms to perform plumbing work in large units being fabricated in a factory and later assembled into high-rise residential buildings," he said. "The use of non-licensed personnel to perform plumbing work in high-rise buildings was never permitted before."

"We brought this error to the attention to the DOB in a meeting on Dec. 19, 2011," he continued. "Attending were representatives of the licensed trades and the highest-ranking officials of DOB. DOB stated that it was not its intent to change the clear provision of the New York City Building Code. DOB said it would reissue the Bulletin to make clear that plumbing work must be performed by employees of licensed firms. Over the next 12 months, we repeatedly requested the issuance of that revised Bulletin or, if DOB changed its mind, an explanation of why DOB thought that high-rise modular construction was exempt from the direct employ Code provisions. DOB did neither."

After that December meeting, O'Brien recalled, "Some of our contractors said, Oh, yeah, Forest City Ratner reached out to us. They said, 'No, no, no. We took care of that at the Department of Buildings. Only the site work has to be done by employees of licensed firms.'"

"Clearly, there was interaction between the developer and the Buildings Department to change how they read the code," O'Brien said.

"I don't think it's a matter of interpretation... All I heard today was a lot of tap-dancing, I didn't hear a straight reason," he said of the DOB's relatively brief testimony. He scoffed at analogies to fabrication of a boiler or a jacuzzi: "This not a boiler... this is a unit with a life safety system, electrical work, plumbing work, fire suppression work. They can't change the code. That's what you guys are for."

"Something or somebody changed their mind, and I can only believe it was for cost-savings reasons," he said. "It certainly wasn't for safety reasons."

"Ratner," uttered one Plumbers Union member.

O'Brien said the cost changes were "minute" given the overall savings planned. Then again, Murphy, when I queried him, said that a building the size of B2 would typically have 30 to 40 plumbers on site but in this case only would have about a dozen, doing the connection work that can't be done in the factory.

Murphy told the committee: "Each and every time my organization has a conversation with Forest City, we asked Who's the licensed plumbing firm? They said, That's been worked out. Each and every time, it's been worked out. So we're here today to find out with whom."

"Bloomberg," uttered a plumber.

What DOB said

Two DOB officials constituted the first panel. Dilan asked if licensed professionals were required.

|

| Fariello (l.) and Sehgal (c.) |

Dilan asked if the agency was prepared "for handling this different type of housing?"

"I think we're prepared for with this full process," First Deputy Commissioner Thomas Fariello responded. " We may have to ramp up our folks when we get more of these [towers] coming to us. We have a high-rise [inspection] unit, and they're going to monitor all high-rises, as they're going up. We're going to have them relate to, it's coming in a box and coming off a crane... I think we're well suited."

Fidler asked what research the DOB had done on the structural integrity of modular construction.

"This was a concern of ours," Fariello said, regarding B2. "We had a structural engineer do what's called a peer review... another engineer that we approved to do a review of the first engineer's work."

Council Member Brad Lander, who said it was important to have more clarity during this moment of technological change, asked for more information about that additional engineering review. Fariello said he'd provide it.

The DOB: temporary rule lingers

"As I understand it, the rule is temporary," Lander said, "and went along with a rule-making process that's supposed to lead to a final rule. Am I right about that?"

"Yes," Fariello replied. "We didn't get to the rule yet. The Bulletin is what we've been using."

"You're in the process of developing a rule," Lander continued. "Do you have a sense of when the rule will be promulgated?"

"No," Fariello replied. "I can get back to you."

"Will the rule look differently or more thoroughly at the possibility of high-rise modular?" Lander asked.

"Yeah," Fariello replied. "When the bulletin was created, there was no one contemplating high-rise to us. So, as we evolve as a department, as new ideas come to us, new projects, we're certainly going to have that in mind." (Note that, if Forest City had not formally presented plans for modular in April 2011, they had surfaced in the press.)

Lander observed that, if the department needs additional resources, Council should make sure they're provided: "We need a final rule in place that does contemplate high-rise modular."

Querying Forest City

Why had no one else tried modular high-rises in New York?

It required significant investment and time, responded Cotton.

|

| Council Members James (l.) and Elizabeth Crowley |

"We had some work going on in the Navy Yard during Sandy," Cotton responded carefully. "We're certainly aware of the impacts that the storm had. Our factory wasn't complete, I think there are lessons to be learned."

"This project was subject to a state environmental review process," James noted. "Was there any environmental review with respect to modular housing"

"Not that I'm aware of," Cotton responded. "The environmental. review was done many years ago. At that time, we weren't planning this tower this way."

She noted that the steel for the tower is manufactured out of state, at Banker Steel in Lynchburg, VA, but that's "noxious, industrial sort of work" not typically done in New York.

Asked to comment on a news report that deemed modular construction ambitious and risky, Cotton responded, "It's ambitious, we don't think it's risky."

Steel vs. concrete

Sanna said Forest City and its partners examined the modular tower in Wolverhampton, UK, that's currently the world's tallest modular.

"We are using structural steel brace frames and then bolting the modules and connecting those modules together; they're using a concrete core," he stated. "We felt there were many more routes for discrepancy, the steel-to-steel tolerances could be much more exact." He noted that the steel chassis and brace frame are both being made by Banker Steel.

Forest City's plans to not use concrete drew critical testimony from Joseph Kaming, representing the Cement League, an associations of union contractors that put in place structural concrete. (His testimony was seconded by the United Cement Masons' Union.)

"All can celebrate new thinking," he stated, but argued that tall modular buildings exacerbate some of the problems--fire safety, durability--seen in smaller modular buildings.

The city, he said, "should thoroughly review and establish specific individualized standards for tall modular buildings if they are to be permitted. Such construction is unique and does not fit into the existing Building Code."

He said toxic, fire, and electrical testing was needed, as would be "fire channeling or chimney effects peculiar to stacked construction." He requested an environmental impact statement as a precondition to any application or permit approval, full compliance with existing code, and a new Building Code section regarding modular construction.

"We do not believe the Buildings Department has conducted a legal and proper review of the Atlantic Yards' 32-story residential tower which would justify its approval," he said.

Asked if his organization had filed a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request for details about the tower, Kaming said the DOB didn't answer. He said the Cement League recognized that pursuing the issue with a lawsuit could jeopardize relations for some members, which deal with DOB regularly.

"When you start transporting something that is 14 feet wide and 35 feet long," he said of the modules, "and begin to lift it in a structure, with wind considerations, that is an entirely different matter. You probably are aware Forest City Ratner has specifically identified the dimensions of the system so they don't have to hire a licensed rigger... because a licensed rigger would add to their cost."

Kaming acknowledged that modular units have their place, but deserved an independent review. "That's why an environmental impact statement, if in fact they had been honest and talked about modular housing," he said, "would have had to include modular housing at the outset. Because it's a different category of structure."

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar